The Lion King is a better Hamlet than Hamlet

Insofar as my blog is known at all - I’ll have you know that I have tens (tens!!) of monthly visitors - it’s known for pictures of birds and chapters of a goofy mystery novel, not hot takes. Well, that’s all about to change, as I have a take so hot you could fry an egg right on there: Disney’s The Lion King is a better Hamlet than Hamlet itself.

It’s well known that the Hamlet was one of The Lion King’s principal influences, and if you didn’t know that, just consider the plots: in both works, the prodigal son of a murdered king seeks (and eventually gets) revenge from his usurper uncle. There are many analogous characters: Simba is Hamlet, Mufasa is King Hamlet, and Scar is Claudius. Gertrude and Ophelia get much more positive portrayals in Sirabi and Nala, as does the foolish toady Polonius in Zazoo. Other characters are a bit more a stretch, like Timone and Pumba as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (Timone and Pumba are pals with Simba, but they don’t spy on him at the request of the king, and neither does Simba arrange their murder at the hands of the English), but still plausible. On the other hand, many characters do not overlap clearly, like Laertes, Fortinbras or Horatio in Hamlet, or in The Lion King, the hyenas, Rafiki, and the gopher who says “Sir, news from the underground!” which as everyone knows is the best joke in the entire movie.

This is the first reason that The Lion King is better than Hamlet: The Lion King is much funnier. There are exactly 3 funny jokes in Hamlet. The first one is when Polonius introduces the actors as “The best actors in the world, either for tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral, tragical-historical, tragical-comical-historical-pastoral, scene individable, or poem unlimited”. I think you will agree with me that this is hilarious, though my students never do. The other two good jokes both come from the same character: the gravedigger. The gravedigger, while wondering why Ophelia (who may have committed suicide - i.e., died sinfully) is to be buried with Christian rites, asks his partner: “How can that be, unless she drowned herself in her own defence?” Good stuff, good stuff. And, just a few lines later, he and his partner have the last funny exchange in the play, which is a pun on the meanings of arms:

First Gravedigger: There is no ancient gentleman but gardeners, ditchers, and grave-makers: they hold up Adam's profession.

Second Gravedigger: Was he a gentleman?

First Gravedigger: He was the first that ever bore arms.

Second Gravedigger: Why, he had none.

First Gravedigger: What, art a heathen? How dost thou understand the Scripture? The Scripture says 'Adam digged:' could he dig without arms?

I cannot begin to count the good jokes in The Lion King, but suffice to say there are many. Nathan Lane is hilarious as Timone the meerkat, but the best comic performance is Nathan Lane’s Pumba. Watch these two clips and tell me otherwise, I dare you:

So The Lion King is funnier. Sure, you might say, but Hamlet is not trying to be funny, it’s trying to be Great Literature; it is Serious Drama. Maybe - but even Serious Drama has to be drama - that is, have a coherent plot. A cursory examination of the plot reveals Hamlet to be a bloated, absurd, and melodramatic mess.

Hamlet begins after the King Hamlet’s murder, and Claudius’s marriage to his wife, Gertrude. Hamlet, now 30 years old, has returned from university to attend his father’s funeral, and finds himself troubled by his mother’s remarriage and the fact that he keeps imagining her and his uncle having sex. Hamlet then sees a ghost of his father (who’s been wandering around the castle at night, scaring guards), who tells him to avenge him. Hamlet does, eventually, but first he’s got to spend three interminable acts behaving as though he is insane, yelling at Ophelia, making snide comments to everybody, talking to actors for a really long time, and putting on a play that is supposed to make Claudius admit his guilt. Hamlet also spends a lot of time wandering around pondering existential questions. Before getting his revenge, he gets sent to England, arranges for the death of two good friends, gets captured by pirates, and makes his way back to Denmark, where he talks to a gravedigger, interrupts a funeral (the funeral of Ophelia, who may-or-may-not-have killed herself after Hamlet semi-accidentally murdered her father Polonius - sorry, I forgot about that whole bit - that’s why he got sent to England, sort of, and it’s also when Ophelia spends a couple scenes wandering around and singing in a deranged manner). Then, Hamlet FINALLY gets his revenge, though he does so by participating in an elaborate duel which ends up killing everyone, including himself, his mother and his uncle. Then some Norwegians show up and, mystified, decide to give Hamlet a soldier’s funeral, despite the fact that Hamlet has never been a soldier.

Of all of these characters, I relate most to the Norwegians. They stumble on a mess, and have no idea what to make of it, for, frankly, Hamlet makes very little sense. I’m teaching the play currently, and having not read it since high school, I’d forgotten all of the really bizarre scenes - especially the ones where Hamlet endlessly talks to the actors, or acts crazy around Polonius, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. I think most people’s memory of the play is a couple soliloquies, the ghost scenes, the part where Hamlet almost kills the king while he’s trying to pray, and Act 5. If you had only those scenes, sure - this is a great play. It asks big questions, presents compelling characters, and you could stage it in less than 2 hours. As the play actually is, it would take 4, and most of those two extra hours are just ridiculous exposition about the machinations of the Norwegians, long, boring discussions of what makes good acting (including examples drawn from the speeches of other plays), and a lot of Hamlet stomping around acting crazy and making uncomfortable jokes about how quickly his mother remarried. It feels like an exploratory draft; Shakespeare needed a good editor on this one.

The Lion King, by contrast, is a tight 89 minutes. Also, despite covering a much longer period of Simba’s life (it’s longer even before adjusting for the average lifespan of lions; Simba begins the movie as a newborn, and ends it as a young adult, approximately three years later), the plot is much more focused. I won’t recap the plot; obviously, that’s unnecessary. Suffice to say that while there are some songs and side adventures that aren’t strictly tied to the main revenge plot (like “I Just Can’t Wait to be King” and the excursion to the elephant graveyard), they are short, closely connected to the movie’s themes, and also do important character work, like introducing the hyenas, Banzai, Shenzi, and Ed, and their scheming with Scar. Every scene in the movie has a discrete, comprehensible purpose, and none go on too long. The same cannot be said of Hamlet - this, after all, is a play which features at least three separate soliloquies in which Hamlet vows to get his revenge.

Sure, sure, sure, I can imagine you saying - but what about the ideas? One common criticism of The Lion King is (or at least it might be - to be honest, there are no common criticisms of The Lion King because everyone loves it, and no one except for me cares about its relationship to Hamlet) that it Disneyfies Hamlet - that by removing most of the tortured psychological musings, the Oedipal overtones, and the tragic ending, the movie sanitizes and brightens a play that is as gloriously dark, complex, and confusing as the human psyche itself. Hamlet, you might argue, is confusing because being a human being is confusing: we are mortal creatures with limited perspectives but infinite minds, and in our imagination, we seek to comprehend the incomprehensible aspects of our existence, especially death, that “undiscovered country from whose bourne / No traveller returns”.

If this straw man somewhere breaths, he is wrong. The Lion King is no less flinching than Hamlet in its examination of death. Coming to understand death and its relationship to life is a primary concern of the film, and it is the primary development in Simba’s character.

Consider the famous “everything the light touches” scene:

Mufasa’s lesson here is that death is a part of life. The sun is a symbol for life, and as Mufasa says, “a king’s time as ruler rises and falls like the sun” - one day, “the sun will set” on Mufasa’s time, and rise for Simba. This cyclical process - or perhaps, I should call it a circle, hmm, perhaps a circle of...life? - includes both death and life. As Mufasa explains when Simba notes that lions eat antelopes, “when we die, our bodies become grass, and the antelope eat the grass, and so we are all connected in the great circle of life”.

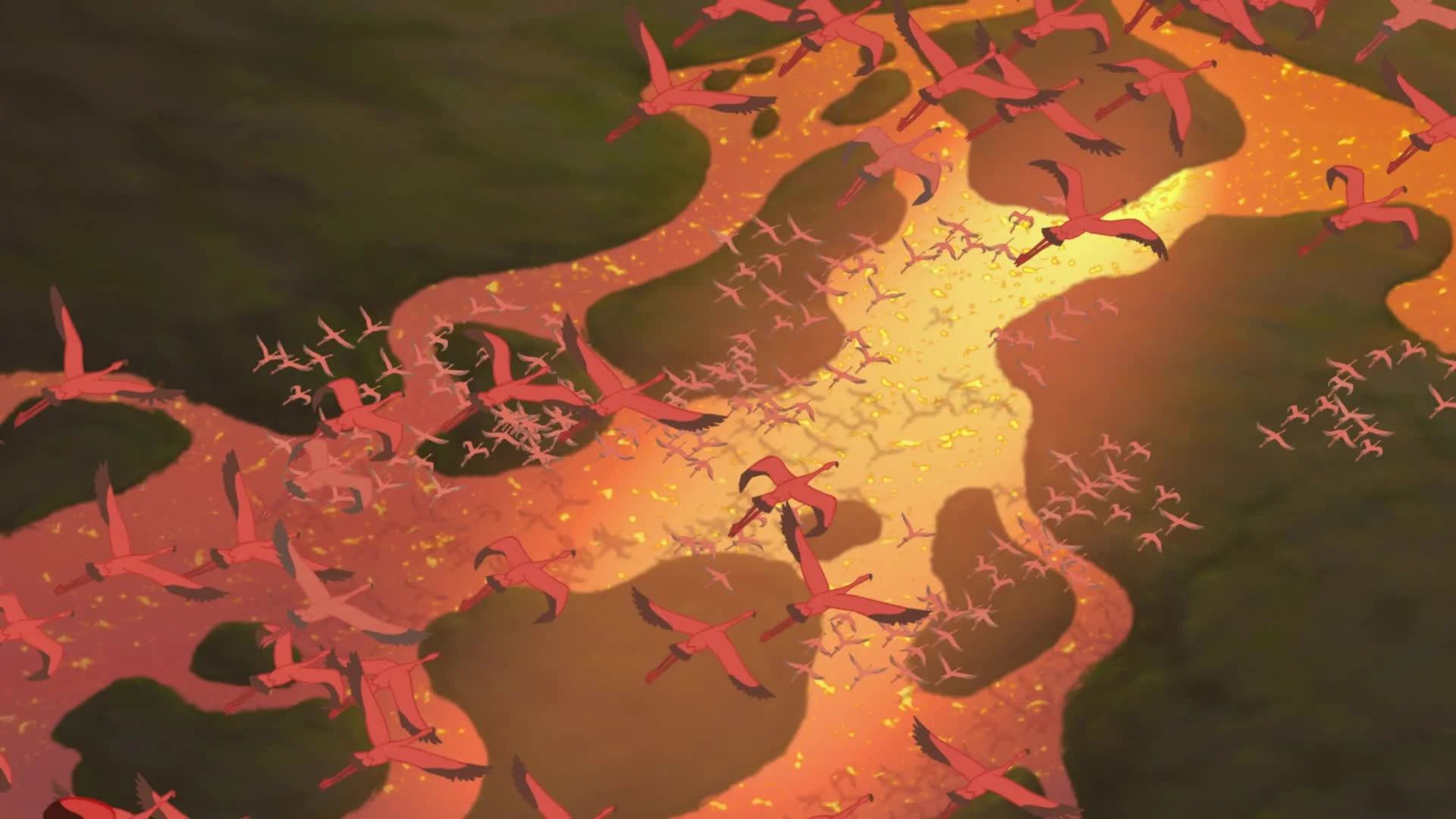

And yet, despite death’s centrality to the lions’ benevolent and orderly Rota Fortunae, there remains an eerie strangeness to death, at least to Simba. The film represents death in several ways, the first of which is in the previous clip: The Elephant’s Graveyard. That “shadowy place” where the light doesn’t reach is “beyond our borders” - not even a king, who “can do whatever he wants” can travel into death without consequences.

This image shows Simba’s understanding of life and death in a single frame: note the contrast between the warm light of the sun, and the cooler grays of the “that shadowy place” across the river, which I guess is supposed to represent the River Styx?

Young Simba does not immediately understand Mufasa’s semi-symbolic lesson about the nature of death, and (with Scar’s manipulation) brings Nala (and, in an echo of Hamlet’s murder of Polonius, Zazoo) to the Elephant’s graveyard. Even before the hyenas arrive, the imagery of the Elephant Graveyard is dark and filled with bones, and the young lions immediately (if childishly) wonder about big Hamlet-esque questions. Simba seeks to demonstrate his courage in the face of death (“I laugh in the face of danger” he blusters, just before the hyenas begin laughing), and Nala wonders what survives when we shuffle off this mortal coil: looking at an elephant skull, she wonders “if its brains are still in there”. When the hyenas arrive, the tone becomes even darker, especially when Simba slashes one of the hyenas across the cheek. This moment, especially the sound of the hyena growling, has stuck in my mind since childhood; it’s a huge tonal shift for the film. The images of the graveyard indicate Simba’s fear of and inability to understand death: they are hellish, dark, and eerie.

The analogous scenes in Hamlet might be King Hamlet’s ghost describing death to Hamlet:

But that I am forbid

To tell the secrets of my prison-house,

I could a tale unfold whose lightest word

Would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood,

Make thy two eyes, like stars, start from their spheres,

Thy knotted and combined locks to part

And each particular hair to stand on end,

Like quills upon the fretful porpentine:

But this eternal blazon must not be

To ears of flesh and blood.

So, in both the film and the play, death is scary. For Simba, death is scary because he is young and does not understand it, and when he first sees death - not just its shadow, the elephant graveyard, but death itself - it is the traumatic death of his father in the gorge.

Notice the dead tree appearing in this scene. This image comes from the blues and grays of the elephant graveyeard, and these eerie colors (a contrast to the warm sunlight that symbolizes life in this film) symbolize the fearsome strangeness of death. These colors and images appear throughout the film: in the graveyard, in the gorge, in the Pridelands when Scar takes over, and several other times throughout the film. Always, when these images appear, the score supports the eeriness of the imagery.

They even occur in the beginning of the the famous “Remember who you are!” scene. Watch carefully as Simba follows Rafiki to the pool:

To speak with his father’s spirit, Simba must travel through a jungle filled with eerie images, images that remind the viewer of both the tree in the gorge, and of the elephant graveyard generally. To understand death and face it with equanimity, Simba must first pull himself through his fear of death. Only then can he learn the film’s truth: that the spirit is eternal for his father lives in him. Indeed, Simba sees his father by “looking harder,” as Rafiki says, into a reflection of himself. If we face the fear of death within us, we can find our soul and our destiny in there too.

This scene contains the film’s most direct reference to the play, and the differences between this scene and its equivalent in Hamlet reveal the most important difference between the two: The Lion King is optimistic whereas, at its core, Hamlet is nihilistic. In the film, Mufasa’s spirit tells Simba that “You have forgotten me...You have forgotten who you are, and so have forgotten me.” Mufasa’s ghost ends the speech with “Remember who you are!” a line that has stuck with me since seeing the film as a child. Now, I see it as an echo of King Hamlet’s ghost, who ends his conversation with Hamlet with “Remember me!” This basic human longing - to be remembered - is a longing to live on after death, a longing, in other words, to escape death’s obliteration. Both Mufasa (which, by the way, means king in Swahili) and King Hamlet share this longing, but more importantly, so do Hamlet and Simba. The ghosts may not even be real, whatever that means when we’re talking about a fictional movie about talking lions based on a fictional play about nonexistent Danish royalty - these ghosts, whatever else they are, are expressions of Simba, Hamlet, and our own anxiety about death.

Accordingly, this conversation restores Simba’s faith in the circle of life, and he runs immediately to fulfill his “place in the path unwinding”. The Lion King is the story of a young lion who fears death, and then faces it - and discovers that death, while scary, is good, that the spirit lives on in a great, harmonious circle. In The Lion King, death isn’t so scary after all, once you really look at it.

Hamlet is different. It is also the story of a young man coming to face his mortality, but when he comes face to face with his dead father in the first act of the play, the experience raises huge, basic questions in him: What happens when we die? What part of us survives death? If we can’t understand death, how can we understand life? How can we have meaningful lives if they end in death? How can we make moral distinctions or meaningful decisions in the face of morality’s oblivion? These unresolved questions explain his tortured behavior (and, by extension, the tortured structure of the middle three acts of the play).

Eventually - especially in the gravedigger scene - Hamlet comes to accept the absurd, even humorous, unknowability of life and death. Let’s not take our lives and deaths so seriously, he realizes as he gazes into Yorrick’s eye sockets, and then, with the stakes lowered, can Hamlet finally act, achieve his (now much less meaningful/egotistical) revenge, and accept his mortality. It is not a coincidence that the funniest character in the play (the gravedigger) is the one who has the most “easiness” with death, nor is it a coincidence that the play ends just one scene after Hamlet meets this man. Hamlet never understands death, but when he is able to look it in the eye calmly, the play (and Hamlet’s inner turmoil) can finally end.

So both Hamlet and Simba face death, but in The Lion King, death makes sense. In Hamlet, nothing makes sense - and that includes death. Now I know I’m arguing that The Lion King is better than Hamlet, but here Hamlet’s metaphysics correspond much more closely to my beliefs than The Lion King’s. I have a strong intellectual bias towards the unanswered question, the ineffable feeling of resolution rather than the concrete bullet point, and the explanation that’s not really an explanation. But there’s a part of me - perhaps some part of me left over from my first few times watching The Lion King - that really, really wants Mufasa to live on within Simba’s shadow, to emerge from the clouds in a time of trouble to help Simba achieve his destiny. I can’t actually believe in that sort of spiritual positivity, but I can’t help but wish it were so simple and reassuring. So sure, Hamlet is more complex, provocative, and (I think) honest in its examination of life and death than The Lion King. But The Lion King is still better, and not just because of the jokes. The real reason is the songs. I mean just listen to this, and if you can tell me that there’s something better in Hamlet, well, you’re a got-dammed liar.