Grammarly, Automation and Teaching English

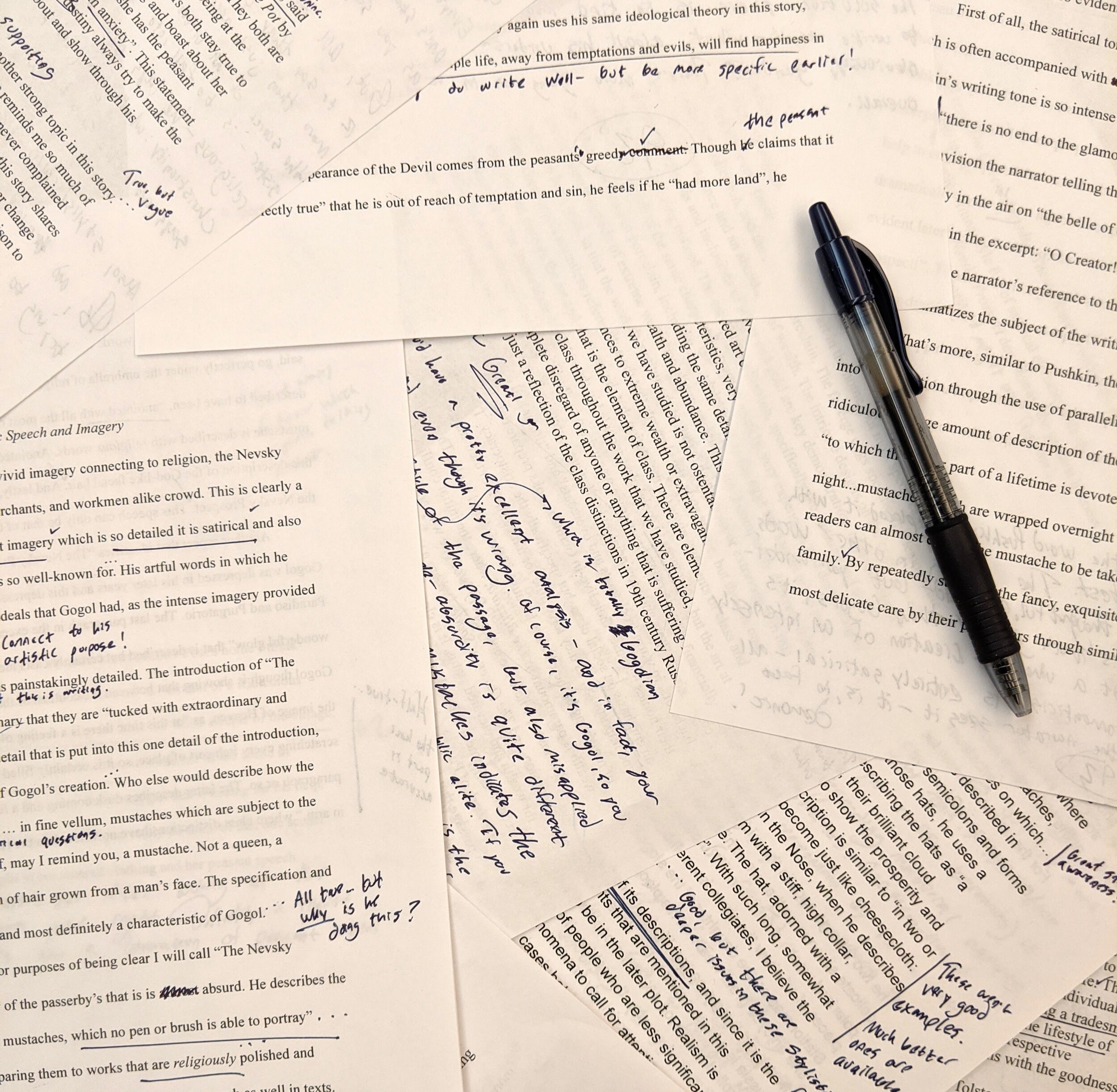

As any English teacher would attest, grading essays does not tend to produce epiphanies - generally, the only epiphany I’ve gotten while grading is that I should consider another line of work (I’m kidding, of course; I love teaching). However, one recent rainy afternoon, leaning resignedly over a batch of my sophomore’s latest missives, about to encircle an errant citation, I was struck by a sudden and arresting revelation: a robot could do this.

I put down my navy blue pen (like many of my progressive-minded colleagues, I’ve abandoned red pens as a relic of an ancient and barbarous era), and considered this thought. Identifying citation errors is not very hard. The formula for MLA in-text citations is simple, and I know it well, and so I can identify and correct them when they are wrong. Now, I am an English teacher, and so while I have no idea how automated software works or how to build one (except, of course, for my Mushroom Name Twitterbot), I do know what automated software can do - and if automated software can beat me in Chess, fix the lighting in my photographs, identify my face for the NSA, or tell me what songs I’m likely to enjoy, they can definitely correct in-text citations. It just can’t be that hard.

As I sat at my desk, the essay lying ungraded before me, I realized that a robot could do a lot of things that I do for money - or, even if they can’t yet, it’s only a matter of time. Don’t get me wrong - my blue pen thing was a bit of a joke, but I’m actually a very progressive teacher: a teacher who takes student voice seriously, who teaches writing as a dynamic, recursive, social process, and who uses tutoring pedagogy to teach these things, who cares much more about whether a student is engaging in a real and meaningful way with the text than whether their essay’s matching whatever formula I think it’s supposed to follow, who teaches as a good school with excellent colleagues and without testing requirements, who sees their job as primarily inspiring, motivating and challenging students to grow, who thinks a good question is much more valuable than the correct answer, who teaches up-to-date student-centric literature, but who also teaches Chekhov for God’s sake, who leads Harkness discussions, assigns creative projects, who builds close relationships with students, whose classroom is filled with laughter, whose desks are in a circle, or actually a rectangle, but you get it - not rows, who has never once given a multiple choice test, used a scantron machine, or required students to adopt a certain interpretation of literature to succeed, a teacher, in other words, who cares much more about their students and real learning and growth than box-checking, arbitrary testing requirements and other measurable, committee-written nonsense that passes for standards / hinders good teachers in so many schools.

And yet - a robot could still do quite a bit of my job.

This is especially true in grading. I try very hard to make my grading process meaningful and genuine, but a lot of it remains repetitive and formulaic. Students need to learn where to put their citations, to write complete sentences, to incorporate and analyze their quotes, and to structure their paragraphs logically - and all these things are variations of formulaic pattern recognition, albeit of varying complexity, but pattern recognition nonetheless. I've written comments addressing those things hundreds on times, often in the exact same way. And that means an algorithm could learn to do it, or will eventually be able to - and a lot more quickly, accurately, and fairly than I ever could. Grammarly is coming for my grading, and frankly, there’s no way I can compete.

Even more unnervingly, more of my job than grading is susceptible to automation. An algorithmic piece of software could do a lot of tutoring pedagogy, most of which is asking students to reflect on their own work, and a piece of software could do that with all of my students at once, rather than as I do it now, which is one-on-one, over hours of class time. A computer program could certainly teach grammar better than I can - and in fact, I already use Khan Academy and its remarkably well-designed program for just this purpose. I write pretty good student comments, but (just as they can write news briefs and even novels) a computer program could do that too, and even if they weren’t quite as good as mine, they’d be done a lot quicker.

To think that my profession won’t be affected by automation is arrogant, even laughable - the kind of head-in-the-sand attitude that I would say characterizes many professions from lawyers to truck drivers. In fact, the only profession I see taking automation seriously as a threat is real estate agents, who, under assault from a variety of digital startups hungry for their 5-7% commissions, have started paying for pro-real estate agent television ads. These ads depict real estate agents as some sort of cornerstone of our American society, which is almost as silly as when Allstate tried to do the same thing with insurance companies. Absurd. As though I’d pay 3% more on a home - or sell my home for 3% less - just because I want a hefty dose of Karen-energy injected into the process. Thank you, but I’ll use Redfin instead.

And yet, you don’t see me signing up to volunteer for Andrew Yang 2024. Automation will not cost me my job, and if you’re a good real estate agent, you probably don’t have anything to worry about either. Automation will help me do the least efficient, most repetitive and dullest parts of my job faster and better, allowing me to focus on what I really care about: inspiring young people to learn and grow. Same thing with real estate agents - accept lower commissions in exchange for higher volume, and spend more time making buying and selling houses easier and less stressful - and then you’ll sell yet more houses. Correcting my students’ citations matters, sure - but every second I spend on that is a second I don’t spend on something more meaningful and interesting. Still: in schools, we need to see automation coming, and we can’t pretend that it won’t affect us. Especially in areas of education focused on repetitive, formulaic, box-checking kinds of learning, automation will be disruptive, but it will disrupt the progressive paradise of my English classroom as well. At the same time, however, we don’t need to be afraid; we need to be ready to use automation to make our work more meaningful and powerful.

So, robots, please come and help me do a better job grading my students’ essays. If a machine can do part of my job, that’s a part of my job that I’m happy to give up. I’ll focus on the good stuff: working with kids, learning from books, and helping my students grow. In the meantime, however enjoyable writing this post has been, I have grading to do, and many citations to correct before I sleep.